What we don't talk about when we talk about China trade

Canada needs to trade with China, but we should not pretend it is the same as trading with our other partners. The human rights record, the 99.97% conviction rate, the hostage diplomacy, and the surveillance concerns all set China apart. Trading partners are not equal, and that should factor into the calculation.

There is a common refrain I keep hearing: we need to trade with China, Carney knows what he is doing, this is just smart economics. I've heard it put this way: "We have to do what is necessary to ensure the safety and economy of our citizens. If we have to trade with China until we find other trading partners, then that's what we have to do."

I am not opposed to trade with China, but I am opposed to pretending that trading with China is the same as trading with Germany or Japan or even the United States. The question is not whether we trade, but what we give up to do so, and whether we are honest about what we are getting into.

Canada's bilateral trade with China totaled $118.7 billion in 2024. China is our second-largest trading partner. We export canola, crude oil, and minerals. We import cellphones, electronics, and manufactured goods. The relationship exists and will continue regardless of who forms government.

But here is what makes China different from our other major trading partners.

Freedom House, a nonpartisan organization that has tracked political rights and civil liberties since 1973, scores countries on a scale of 0 to 100. In its 2024 report, Canada scored 97 and is classified as "Free." China scored 9 and is classified as "Not Free," ranking 189th out of 210 countries and territories. The United States scored 84. Japan scored 96. These are not abstract numbers, they measure whether you can challenge your government in court, whether journalists can report without disappearing, whether religious practice is tolerated, and whether you can be held indefinitely without charge.

China's conviction rate in criminal trials exceeds 99.97%. In 2019, out of 1.66 million people put on trial, only 637 were found not guilty. This is not because Chinese police are exceptionally good at catching the right people, it is because once charged, the system does not permit meaningful challenge.

Canadians learned this firsthand. In December 2018, Canada arrested Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou at Vancouver International Airport on a U.S. extradition request. Days later, China detained two Canadian citizens, Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor, on espionage charges. Kovrig spent his first five months in solitary confinement with the lights on 24 hours a day. Both men were held for over 1,000 days. On September 24, 2021, hours after Meng signed a deal with the U.S. Department of Justice and flew home to China, both Canadians were released and put on a plane to Calgary. China maintains that the cases were unrelated, but nobody outside the Chinese government believes this.

The Canadian government's own website acknowledges the risks of doing business with China, citing "market access barriers, opaque regulations with uneven and arbitrary implementation, prevalent and persistent intellectual property theft, and the risk of diversion of sensitive goods and technologies."

Beyond the human rights record, there are practical security concerns. Chinese technology firms operate under laws that require them to cooperate with state intelligence agencies when asked [CSIS analysis, full law text]. In October 2024, the Communications Security Establishment stated that Chinese government threat actors "have compromised and maintained access to multiple government networks over the past five years." In June 2025, Canada ordered Chinese surveillance firm Hikvision to cease operations in the country, citing national security concerns.

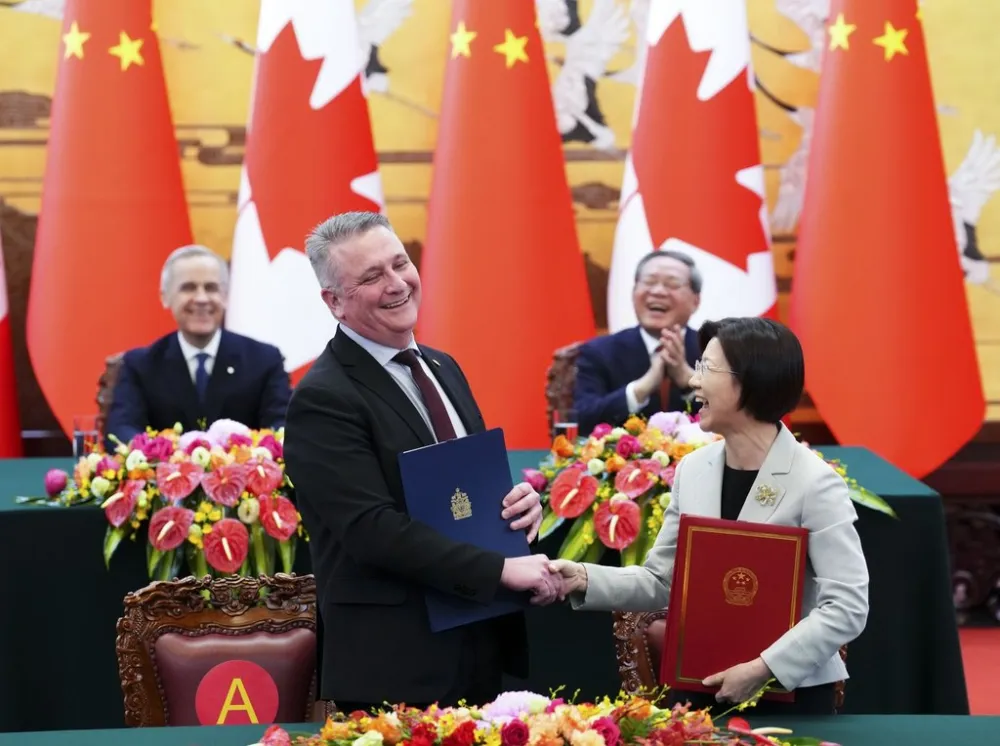

Despite this, the Carney government recently negotiated a deal to allow up to 49,000 Chinese EVs into Canada at a reduced 6.1% tariff, exempt from the 100% surtax introduced in 2024. Carney framed this as securing "new Chinese joint-venture investment in Canada." What Canada gave up in return has not been made public.

None of this means we should stop trading with China, but we should not pretend that deepening economic ties with an authoritarian state that has demonstrated willingness to use hostage diplomacy against our citizens is the same as signing a trade deal with Norway.

When people say "we have to trade with China," I agree. When they say "Carney is being pragmatic," I want to know: pragmatic about what, exactly? Trading partners are not equal. Some of them will take your citizens hostage if you inconvenience them, compromise your government networks for years without detection, and integrate surveillance technology into the products you let through your borders. That should factor into the calculation.